Parashat K’doshim Study Guide Themes

Theme 1: Bringing Holiness into Everyday Life

Theme 2: Bringing Holiness into the Home

INTRODUCTION

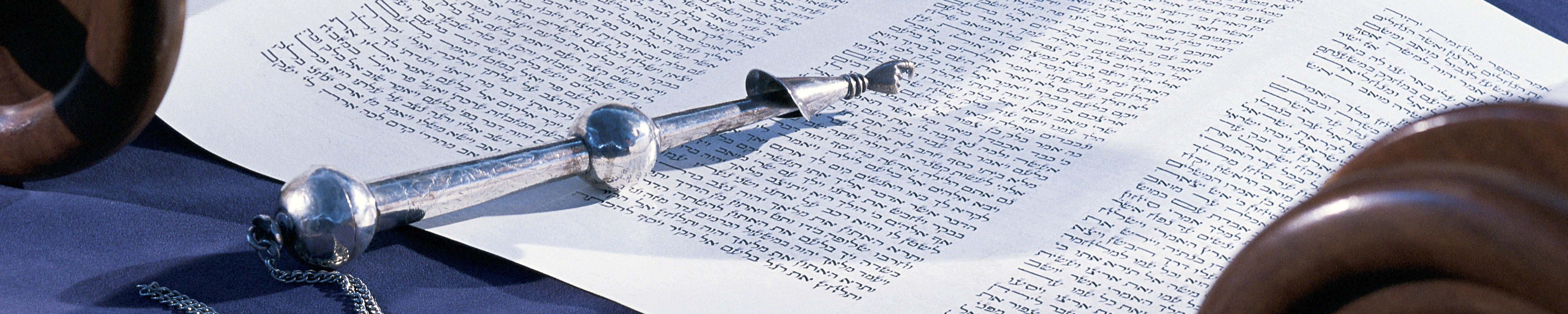

The word k’doshim (“holy”), which is the title of this parashah, is found in various forms fifty-nine times in Leviticus 17–26. Scholars refer to this part of the book of Leviticus as the Holiness Code because of its emphasis on what human beings must do to strive toward holiness in all aspects of life. Although many of the laws in parashat K’doshim appear elsewhere in the Torah, their repetition here, according to biblical scholars, suggests that the Holiness Code was written by priests who were influenced by the eighth century B.C.E. prophet Isaiah (for more details, see The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, pp. 568, 703). If we view Leviticus 17–26 through this lens, the Holiness Code is a response by an anonymous group of reform-oriented priests to the writings of an earlier group of priests whose perspective is reflected in Leviticus 1–16 and in other parts of the Torah. The commandments in Parashat K’doshim concern people’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings in the home, in business relations, and in worship. Although these laws echo those found in the Ten Commandments, the laws in parashat K’doshim—unlike the Decalogue—begin with those that emphasize the relationships between human beings, rather than between human beings and God. Parashat K’doshim teaches that preserving holiness is about emulating God (“You shall be holy, for I, your God YHVH am holy”) by bringing holiness into the families and communities in which we live.

BEFORE GETTING STARTED

Before turning to the biblical text and the questions presented below, use the introductory material in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary to provide an overview of the parashah as a whole. Draw attention to a few key quotations from the introduction to the Central Commentary on pages 701–2 and/or survey the outline on page 702. This will help you highlight some of the main themes in this parashah and give participants a context for the sections they will study within the larger portion. Also, remember that when the study guide asks you to read biblical text, take the time to examine the associated comments in the Central Commentary. This will help you answer questions and gain a deeper understanding of the biblical text.

THEME 1: BRINGING HOLINESSINTO EVERYDAY LIFE

It is clear from the beginning of parashat K’doshim that the laws that follow are for the entire community, not only for priests operating in the world of the sanctuary. This more egalitarian view of holiness moves beyond the idea that only certain people, places, and times can share in God’s attribute of holiness. The world of parashat K’doshim is one in which social and economic justice, protection of the vulnerable, and proper handling of anger in action and thought are keys to making God’s holiness manifest in the world.

- Read Leviticus 19:1–2, which describes God’s command to Moses regarding the laws that follow.

- God’s command to Moses in verse 2 to “speak to the whole Israelite community” is the only time in the Torah that God instructs Moses in this way. This stands in contrast to the more common language in the biblical text in which God instructs Moses, who then carries out the divine instructions. What does this suggest about what is to follow?

- In the first command to the people (v. 2), God instructs, “You shall be holy [k’doshim].” The word k’doshim comes from the Hebrew root k-d-sh, which also means “to be set apart” or “to be consecrated.” What does it mean to you to “be holy”? What do these additional meanings of the root k-d-sh add to your understanding of the term k’doshim?

- According to verse 2, why should the people be holy? How does this compare with the reason that people should be holy according to Deuteronomy 7:6 (where the word translated as “consecrated” is kadosh, the same as the word for “holy” in v. 2)? According to the Central Commentary on Leviticus 19:2 (p. 704), how does the priestly understanding of holiness differ from that found in other parts of the Torah (like Deuteronomy 7:6)? What is the view of the priestly writers about holiness in relation to God?

- The purpose of following God’s laws, in the view of the priestly writers, is to maintain boundaries between the holy and the unholy, thus ensuring God’s presence in the sanctuary. In earlier priestly writings the view of holiness is static, while the Holiness Code presents holiness as dynamic and constantly shifting according to our actions in the world. How does this shift in perspective democratize holiness, according to the Central Commentary? What is the significance of broadening the view of holiness to include the people as well as the whole Land of Israel?

- Read Leviticus 19:9–16, which outlines laws pertaining to economic justice and to exploitation, both between fellow Israelites and in courts of law.

- What do verses 9–10 command the people to do, and what is the reason for this command? What is the rationale for this command, according to the Central Commentary on this section (p. 705)? What does this command acknowledge about the distribution of wealth?

- What is the command in the first part of verse 11? How does this command connect the Holiness Code to the same command in the Decalogue (Exodus 20:13)? To what does the Hebrew word ganav (translated in Leviticus 19:11 as “steal”) refer, according to the Central Commentary on this verse? What are the two cases in the Bible of women stealing, and what motivates these acts of theft?

- What do the prohibitions in verse 14 regarding the deaf and the blind have in common? In your view, why does the command to “fear your God” come immediately after these prohibitions?

- The word translated as “basely” in verse 16 comes from the root r-k-l, which means “to go about from one to another,” either to trade goods or gossip. What is the message the Torah teaches in this prohibition regarding the misuse of speech? What is the relationship, in your view, between misuse of speech and the other prohibitions in these verses?

- The second part of verse 16 is translated here as “Do not profit by the blood of your fellow [Israelite].” How do the other translations of this phrase offered in the Central Commentary change your understanding of the prohibition?

- Read Leviticus 19:17–18, which contains commands about how to handle anger in action and thought.

- What do the commands in verses 17–18 suggest about how the biblical writers felt about the difference between behavior that human beings can monitor and enforce and feelings and thoughts that only God can “see”?

- The word translated as “hate” in verse 17 describes both how people feel and what people think. How do the commands in verse 18 portray the relationship between feelings, thoughts, and actions? What does this suggest about the understanding of the biblical authors about the relationship between emotions, thoughts, and actions?

- According to the Central Commentary on verse 17, what are the various ways that we can understand the clause “incur no guilt on their account”? What does each interpretation bring to your understanding of the text?

- The verb for “love” in verse 18 is followed by the preposition using the letter lamed. We find this form only four times in the Bible, and in all four cases there is an implication of action, rather than just feeling (see Leviticus 19:34, where we find the command to love the stranger as yourself). In your view, why does this command follow immediately after the first part of verse 18?

- Our translation of verse 18 inserts “Israelite” after the word translated as “fellow.” Other translations often render the phrase “fellow [Israelite]” as “neighbor.” How does verse 17 provide the basis for the present translation? What impact do each of these translations have on your understanding of the behaviors that these verses command? How can we use the commands in these verses to guide us in our interactions with others, both within the Jewish community and outside of the Jewish community?

- Read the Another View section by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi (p. 716).

- While biblical definitions of holiness frequently encompass separation and distinction, Eskenazi argues that holiness comes from connection. How do you understand the contradiction between these two views of holiness? How does Eskenazi’s perspective on holiness expand your understanding of this core biblical concept? Based on your own experiences and your reading of the biblical text, which interpretation rings true to you?

- Of the three times God commands Israel to “love” in the Torah, two are in this parashah (19:18, 19:34). What is the difference between the “objects” of love in these two commands? According to Eskenazi, what is the rationale for loving the stranger? What ramifications does this rationale have? What do these commands to love God teach us about the relationship between loving God and loving others? The reason given for the command to love the stranger (19:34) is because we were strangers in Egypt. Can you think of a time in your own life when this command inspired you to speak up or to act on behalf of those in our society who are vulnerable?

- According to Eskenazi, how does the story of Ruth the Moabite serve as an exemplar of what it means to love?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Ruth H. Sohn, on pages 716–17 (“You shall be holy,” “Do not deal basely . . . ,” “Reprove your kin . . . ,” and “Love your fellow. . . .”).

- How do Rashi and Nachmanides understand the command in 19:1 that “you shall be holy”? What challenge presented by parashat K’doshim precipitated these comments?

- What connection do the Rabbis make between the command in 19:16 to “not deal basely with members of your people” (see 2.d above) and the concept of l’shon hara (evil speech or gossip)? What are some contemporary examples of how l’shon hara can damage the three parties identified by the Rabbis? Can you think of an example in your own life when l’shon hara damaged these three parties?

- According to BT Arachin 16b and Midrash B’reishit Rabbah 54.3, what does the double verb in the first part of 19:17 teach us (“You shall [surely] reprove your kin . . .”)? Why is the command to rebuke doubled, according to the Talmud? According to Ibn Ezra and to BT Shabbat 54b, why should we confront a wrongdoer? What does Jewish tradition teach us about what to do if the person we confront does not listen? What is your view on whether (or how) we should confront authority figures such as teachers, parents, or employers? How does the command in 19:17 inform your views?

- What does the command to “love your fellow [Israelite] as yourself” (19:18) teach us, according to Ibn Ezra? How should we express this love, according to other rabbis? What is your reaction to Rabbi Akiba’s view that this is the most important teaching in the Torah?

- Read the Contemporary Reflection by Elyse Goldstein (pp. 718–19).

- According to Goldstein, what does parashat K’doshim tell us about who is included in the command to be holy? How does Rabbi Moshe Alshech understand the reason that such important rules are taught to one large assembly, rather than individually?

- What are the implications of the verb tih’yu (19:2) about when we are to be holy?

- Why are we to be holy, according to Goldstein? How does the Latin term imitatio dei help us to understand this command? In imitating God, how do we achieve a higher sense of purpose? How does parashat K’doshim place the responsibility for holiness on us, rather than exclusively on God?

- Goldstein notes that although the parashah describes the specific actions that constitute holy behavior, it never defines the word kadosh (“holy”). Rashi and other commentators understand the command to be holy as a command to be separate from others (see 20:26). How does this concept of separation apply to the classic Jewish marriage formula? How does the Talmud’s concept of hekdesh help you to understand the relationship between being holy and being separate? According to Goldstein, how is holiness linked to separation in Judaism?

- Goldstein notes that the concept of separation is critical in understanding Jewish spirituality. How might the fact that separation is an important element in Jewish spirituality be challenging for women and for the way in which women experience holiness? According to Goldstein, how does Rashi’s view of kadosh as “separate” present a fundamental feminist challenge? How can redefining mitzvot as connectors rather than as boundaries help us meet this challenge? How can Eskenazi’s view that holiness comes “from cultivating relationships” help us to broaden the view of Rashi and others that kadosh is about separation? How do the commandments in this parashah support the view that holiness comes from connections?

THEME 2: BRINGING HOLINESSINTOTHE HOME

Parashat K’doshim emphasizes that holiness extends to the private as well as the public sphere. The laws regarding family and sexual ethics in this parashah affirm that in the preservation of holiness, the people’s most intimate interactions and behaviors are as vital as those that others can see. In the realm of sexual ethics, this includes laws prohibiting incest, adultery, and male-to-male sexual acts that confuse sex roles. These commandments begin with prohibitions against insulting one’s parents, supporting the belief that illicit sexual relationships undermine both family and clan.

- Read Leviticus 20:9–12, which introduces laws on family and sexual ethics.

- The verse that opens this unit (v. 9) begins with a prohibition against insulting one’s father or mother. The words translated as “insults” and “has insulted” appear twice in this verse and contain the root k-l-l, which means “to make something small,” “to curse,” or “to dishonor.” In your view, what is the connection between the prohibition against insulting one’s parents and the laws that follow, which concern adultery and prohibited sexual relations?

- What is the punishment for violating the prohibition in verse 9? Why do you think the Torah mandates such a severe punishment for dishonoring one’s parents in this way? The person who insults his father or mother also retains the bloodguilt, the biblical consequence of shedding blood. Retaining bloodguilt means not only that guilty parties receive death as a punishment, but that their executioners are not held accountable for killing them. The literal translation of “bloodguilt” in this verse is “his blood [will be] upon him.” In your view, what is the reason for this additional punishment?

- According to verse 10, what constitutes adultery? What can we infer from this verse about sexual relations between a married man and an unmarried woman?

- A parallel passage to verse 10 (Leviticus 18:20) states that when a man has sexual relations with a neighbor’s wife, both parties are rendered impure. Verse 10 adds that both parties are to be put to death. What can we learn from these passages about the Torah’s attitude toward a woman’s complicity in illicit sexual acts? In your view, what are the possible reasons that 20:10 mandates that the woman, as well as the man, should be put to death?

- How do you understand the description of a man having intercourse with his father’s wife as “uncovering” his father’s nakedness (v. 11)? What do the prohibitions in verses 11 and 12 have in common? According to the Central Commentary on verse 12, what does the Torah state regarding sexual relations between a man and his daughter? (See also the Another View section for Acharei Mot on p. 694 and Post-biblical Interpretations on p. 695: “Do not uncover the nakedness of a woman and her daughter.”)

- Read Leviticus 20:13–19, which describes additional sexual taboos.

- The prohibition in verse 13 concerns a man having intercourse with a man the way a man has intercourse with a woman. According to the Central Commentary on this verse, what is the biblical understanding of the sexual act? How does this help you understand why the Torah contains no prohibition against female-with-female sexual acts? What is the problem, from the standpoint of the biblical authors, with male-with-male sexual acts?

- The Hebrew word zimah in verse 14 (translated as “depravity”) appears only four times in the Torah, two of which are in this verse. This word can also be translated as “evil device” or “wickedness.” What does this suggest about the significance of the prohibition in this verse for the authors of the biblical text?

- What is the difference between the punishments for the man who has carnal relations with a beast (v. 15) and a woman who does the same (v. 16)? In your view, what accounts for this difference?

- Verse 18 uses the Hebrew word davah, which occurs only four times in the Hebrew Bible. This word, meaning “to be faint” or “unwell,” differs from the more common word for a menstruant, niddah. What does the use of the word davah suggest about the concern behind the prohibition in this verse? According to the Central Commentary on this verse, what does this word suggest about attitudes toward menstruation? How does the punishment for a man who lies with a menstruant in this verse compare with the punishment for the same act in 15:24? According to the Central Commentary, what accounts for these differences?

- What prohibition does verse 19 address? How is having sexual relations with one’s aunt “laying bare one’s own flesh”?

- Read Post-biblical Interpretations by Ruth H. Sohn on page 717 (“If a man lies with a male . . .”), regarding 20:13.

- What are the implications of the two different ways in which Rashi and BT Sanhedrin 54a–b understand the prohibition in 20:13?

- What are the varying views of the Rabbis regarding whether two bachelors can sleep under the same blanket? In your view, why is the Rabbis’ focus of concern bachelors, rather than all men?

- What is your reaction to Maimonides’ view of homosexual relations?

- Although the Torah does not explicitly prohibit sex between two women, the Rabbis address this issue. How do you understand the varying views of the Rabbis regarding sexual relations between women? What is the importance for the Rabbis in the distinction between the male-female sexual act and “mere indecency”?

- According to Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Forbidden Intercourse 21.8), what rules should apply to a woman who engages in sexual relations with another woman? How do you understand Maimonides’ view that husbands should not allow their wives to spend time with women known as lesbians?

- Read “Turning to Rest in Sappho’s Poems” by Agi Mishol, in Voices (p. 722).

- Who are the sexual partners this poem envisions?

- How does the fact that the lovers in the poem are two women influence your understanding of how the lovers “talk about life that makes us thirsty” in the poem’s third stanza?

- How does the lovers’ attitude in the poem honor “all the loved ones / women and men / who came to rest / between our thighs”?

- What is the relationship between the view of sexuality expressed in this poem and the view of sexual relations in this parashah, particularly in 20:13? What does it mean to pair this poem with the biblical text? What influence do the views of homosexuality expressed in 20:13 have on your own views of homosexuality? If your own views of homosexuality have changed over time, what accounts for this change?

Overarching Questions

As you study these parts of the parashah, keep in mind the following overarching questions. If time permits, conclude the class with these broader question:

- According to Eskenazi, parashat K’doshim teaches that holiness comes from connections—from cultivating relationships—not only from separation. Can you think of times in your own life when you felt a sense of holiness through separation? How did this differ from a time when you felt a sense of holiness through connection? How can both separation and connection help us to manifest holiness in our lives and in our community?

- The laws regarding illicit sexual relations in parashat K’doshim begin with a commandment against insulting one’s parents. These sexual behaviors were considered a threat to the family system. The Hebrew verbal root translated as “insults” (k-l-l) in 20:9 also means “to make something small,” “to curse,” or “to dishonor.” How can we use a broader understanding of this verbal root to think about actions in addition to sexual taboos that are destructive to the family?

CLOSING QUESTIONS

- What new insight into the Torah did you gain from today’s study?

- What other new insights did you gain from this study?

- What questions remain?